Using Data for Health Justice

by Daniel Akinola-Odusola & Araceli Camargo

December 2021

Before reading this report please note that we are a grant and citizen supported lab, we use our funding to create free scientific reports, which provide foundational knowledge about health, health inequities, and health justice. We prioritise the hiring of scientists and researchers from marginalised communities to ensure that the lived experience is covered in an ethical, inclusive, and accurate manner.

Our goal is to be an open lab that is “for the people by the people”.

Introduction

Data refers to individual items of information, facts or statistics that can often be communicated in a numerical language. Due to its numerical articulation, data is often perceived as neutral, unbiased, or accurate. It receives these descriptors with little resistance to the contrary, often verging into a dogmatic thinking that data cannot be wrong. This creates a supremacy culture around data, where it rules over other methods of observation such as an individual’s accounts of their lived experience, which is often dismissed as anecdotal or not rigorous enough to count. There is another line to this supremacy culture, which is that those who can conduct this type of work are seen as above those who do not. In the context of community health, this has put millions of people at risk of poor health outcomes.

We have been following two communities in Southall and Staffordshire who are experiencing acute air pollution due to the remediation of land on a former gasworks site and an open landfill site respectively. Although very different communities, there are similarities. Both communities are being told by Public Health England (PHE) they are not at risk of poor health outcomes, PHE is coming to this conclusion based on air pollution data provided to them by the Environmental Agency. Despite PHE’s proclamation, both communities are seeing spikes in hospitalisation, people are experiencing nausea, headaches, problems breathing, chest pains, and various other poor health outcomes.

This divide needs to stop, it is not good enough to simply say “the data says” and walk away as it contributes to health injustice and inequity. These communities are being told that their lived experience does not matter, that their data does not matter, and that their intellect does not matter. The supremacy around data has to change if we are to move towards equitable and Healing Futures.

The mission of this report is to reframe the culture around data to ensure that we understand its limitations, reframe from supremacy to a tool for justice, and introduce a more accurate lexicon so we can better our collective understanding of data.

“it is not good enough to simply say ‘the data says’ and walk away”

Why Health Data?

In the 21st-century, data is a form of currency and a building block with which many people and organisations frame the condition of the world around us as well as ourselves. According to Merriam-Webster Dictionary, data is a “factual information (such as measurements or statistics) used as a basis for reasoning, discussion, or calculation” (source). An important distinction to make is that data itself is an often unstructured set of symbols and/or characters. This essentially means data is not inherently good or bad as those layers are added when data starts to get interpreted. By the time someone uses data to make a decision, present a fact, or justify an opinion, the data has gone through some form of framing to make it meaningful to some stakeholder(s). According to the Data Protection Act of 2018, ‘data concerning health’ is “personal data relating to the physical or mental health of an individual, including the provision of health care services, which reveals information about their health status” (source). Therefore, when we talk about data, we are referring to what is directly being collected as a neutral, apolitical term. But when we mention health data, it is data that can inform and affect decisions regarding our health. While health data starts unstructured like any other data, it quickly becomes valuable and ceases to be apolitical in action.

Healing and Health

In order to pivot from the current data supremacy framework around public health, we have to start with defining health and healing. In western tradition, health has been defined as the absence of disease and healing as its treatment (source), which seems rather reductive. At Centric, we frame health as the phenomena of accessing wholeness, dignity, and safety through an entire lifetime.

We achieve health through the process of healing, which is an ecological process (source). Meaning that we achieve healing through being in relation with our external environment.

Building on this, healing is a lifelong process of being afforded through external support the ability to come back to stability after trauma or stress. For example, if you experience hunger, it would be the ability to access nourishing food, this in turn would stabilise your bodily functions. Or if you experienced the loss of your home, it would be the ability to access social, financial, and structural support that would allow you to be rehoused and build a home again. In this explanation, healing and health go beyond the absence of disease and its treatment, it is about creating a supportive ecosystem that allows a person to come back from trauma or stress.

Understanding that health and healing are in relation to our external environment (source), we have to think systemically and include the expertise of a wide range of people including communities. It also means accepting that data alone cannot provide us with the full phenomenological experience of health. In turn this moves us from a supremacy framework and one of equitable collaboration. Three further perspectives to consider;

We should consider various systemic factors such as where a person lives, the type of work they do, their social infrastructure, their access to resources etc in order to build a more complete picture of health through data.

We should also consider the lived experience, which means that data alone cannot tell us the full picture of a person’s health or ability to heal. To fully capture lived experience, we need to create an equitable data ecosystem where a community can gather their own data and have it be as important as the data gathered by practitioners (source).

Finally, we need to consider that the assessment of health is not “ input out output”. For example a low level reading of air pollution does not inherently equate to low risk to health as the person could be already experiencing asthma or have other biological burdens that even low levels can present a high risk to their health (source).

Data-Driven Health

Society’s increased data generation on personal and systemic levels has led to more data-driven health practices, meaning health data is becoming increasingly valuable to citizens and those who serve them. We can refer to data-driven health as the process of creating health infrastructure that relies on analysing data on individuals and communities in order to create campaigns, policies, and solutions.

For example, taking a test to determine if a prescription or referral to a specialist is needed is data-driven health. Creating a new policy to keep pollutants in line with national or global targets is data-driven health. Since data is itself a neutral tool and its uses vary, data-driven health is neither good nor bad but can become either based on how it is executed. Data-driven health is simply a reality of the way we create modern health knowledge that we need to approach with a critical eye if we hope to move towards health justice and healing.

Injustice and Health Inequity in “Data-Driven” Health

We have to be critical of data-driven health because of the role data can play in creating marginalised communities, cultural asymmetry, and destructive narratives.

The UK COVID-19 response showed some data-based disparities, what the Ada Lovelace Institute refers to as the ‘the data divide,’ which include factors such as service accessibility, digital infrastructure, awareness of technologies, and familiarity or attitudes towards technology (source, source). Many of these outcomes are a result of using data as evidence in a situation where there is already a power inequity and distrust in structural stakeholders.

This inequity can be the difference between asking an open-ended question (such as “how do you spend your evenings?”) and a misleadingly or offensively closed question (such as “how often do you participate in anti-social behaviour?”) to create data that frames a community in a certain light. Sometimes, this is purely unintentional due to a lack of self-awareness on research methods. Other times, it is an intentional power play that is steeped in a culture of supremacy. Regardless of intention, data can become a tool for injustice when it is used on people rather than with people to create a narrative.

Community members of Southall, west London protesting alongside Green Party co-leader Sian Berry, GLA member Caroline Russell and members of Extinction Rebellion against the environmental injustice occurring from local development.

image source https://southallandhayescleanair.org.uk/

Another damaging use of data-driven health is to directly conflict with, or erase, more localised or cultural knowledge that may not present as explicit data.

In the case of the Southall community in London, a Public Health England interpretation of WHO air pollution guidance did not find the construction over former gasworks to be at a level that would cause negative health to the residents.

The demographics of the population were never taken into account, a community investigation supported by Centric Lab produced data to suggest the population had several reasons to have a higher susceptibility including population density and the length of time families spent in an area with medium environmental health risk compared to other parts of London (source).

But external cultural knowledge from a case study such as Southall might inform communities that data taken with a specific method is not applicable in their case.

When “experts” are not self-aware of the limitations of the data that they are using, the results can leave communities underserved and incorrectly stigmatised. We, therefore, have to avoid this form of health injustice.

Justice Paths in Health Through Data

Despite the health injustices data can help propagate, there are positive and impactful paths we can take with health data to support health justice. In fact, there are some promising benefits that come with the use of data in health justice that will frame the rest of this report.

The common outcome of these justice paths is health data complementing localised understandings of health in order to develop more thorough and transferable health knowledge to enable wise and equitable decisions. For instance, if people from a variety of cities and nations are discussing the effects of air pollution, they will have policies, behaviour, physiology, and language that also vary around the experience of air pollution. For instance, providing the right data can be a useful gateway to understanding the global context of the environment someone else is coming from.

Another justice path of health data is formed by creating robust strategies and goals around health justice based on the scale of impact and community involvement. If we look at the example of respiratory health, the appropriate health data can help a community or individual find another community with similar experiences and levels of respiratory difficulty to find out what may be similar about the other and their environment. The initial individual can then learn or share best practices in a way that is more likely to be transferable to the other community’s situation or vice versa. The result of this exchange is a nuanced approach to how we look at global benchmarks and health policies or recommendations.

Thirdly, those who are practitioners can help democratise the access to data as part of healing infrastructures. Communities have a very long and successful history of generating healing justice. From the African American communities putting forward the first case of environmental racism (source) to Turtle Island and Sibling Lands resistance and protection of Land, Water, and Air (source). However, communities often are doing the work with little to no economic or structural support. Therefore, creating toolkits and healing infrastructures can play a key role in supporting communities.

screenshot from the Right to Know project - www.right-to-know.org

Right to Know is a postcode tool that provides communities with data and information about the environmental pollutants in their area and their association to poor health outcomes. This type of data access is crucial in creating equitable Healing Futures as communities can access data that usually costs money or is only for academic use. This data tool also has a platform for town halls, where community organisers are encouraged to engage with the practitioners behind the tool, creating an equitable scientific ecosystem rather than a top down supremacy culture.

Finally, we should collaborate with communities to co-create data tools, so they can collect their own data. For example, there are now various free air pollution monitoring tool kits for citizens to track air pollution in their area. However citizen led data needs to be acknowledged by macro structures, such as by policy makers, if it is to be a successful strategy. Additionally, academic or independent labs should offer analytical support if needed to help communities create their own health reports.

The demand for a culture and infrastructure that enables health justice and healing will only increase as we deal with more global and novel health challenges. The COVID-19 pandemic has demonstrated how data-driven health initiatives can combat pandemics through more accessible outreach, personalised response, and data to inform larger scale strategy (source). The pandemic has also presented challenges misinformation brought to framing health justice and healing (source). Climate change resilience is another instance where data can lead to health justice and healing. The World Health Organisation (WHO) and Center for Disease Control (CDC) have developed resources to help frame climate change (source, source) but true health just would be creating the data points for communities to be able to assess the risk that their current environment and lifestyle pose to their health.

“we should collaborate with communities to co-create data tools“

A New Data Culture & Framework

We need to change the way we think about data and the culture around it, if we are to use it for health justice. Practically, this means the following;

1

We need to rethink the role of data. It is a starting point to help us understand the different relationships between people, health and environments.

2

Health should be reframed as ecological to make data studies inclusive of a community’s lived experience and systemic environmental factors.

3

We should create more ethical and inclusive pathways to gathering and analysing data that reflects the lived phenomena being articulated and experienced by a particular community. This means that if the data is not yet reflecting the poor health phenomena being experienced then data gathering and analysis methods should be reassessed.

The first example is from our with the CASH community (source), who are experiencing poor air quality due to a gasworks site. Public Health England conducted a data study measuring how many students had been absent from school since the gasworks started. They found no spike, therefore concluded the site was no risk to children’s health. However, when we asked the community how often they would keep their kids home due to sickness, most said they couldn’t due to being shift workers and zero hour contract workers. Meaning they could not afford to keep their kids out of school. Therefore, this data study was not a reflection of the phenomena being experienced by the community, so new methods should have been used. (source)

The second example is Covid-19. It took an independent organisation called Body Politic to diagnose long-haul Covid (source). For the first 6 months, doctors and the World Health Organisation were denying the phenomena because at that point the data pointed to Covid being a three week illness with a very specific set of symptoms. This meant thousands of people were incorrectly diagnosed and were not able to get the help they needed.

4

Data should be collected and analysed in collaboration with the community experiencing the poor health outcomes. This is to both honour community sovereignty and to understand the phenomena with more effectiveness.

5

As practitioners we should acknowledge that the scientific method is not apolitical to avoid creating injustices through “well meaning” methods. The scientific method can get political in two significant ways. The first is when an external practitioner is the one making hypotheses and observations in order to make suggestions and changes for a community without consent. They have a very high chance of missing unreported or unexpected details leading to a flawed knowledge base (see point 3A). The second instance is when citizens themselves are not given the technology, time, tools, or resources to understand the phenomena in a scientific language. In turn this impedes practitioner and citizens from open and clear communication. It also prevents the community from engaging in informed consent and decision making, both crucial in ending health injustice.

6

We should move from a top down/supremacy culture; where the practitioner cannot be held accountable by the community experiencing poor health outcomes. The community should be an active participant and/or have avenues to contest data findings within an established framework, such as weekly or monthly town halls.

7

It is important for practitioners to clearly understand the cognitive gap between a data analysis and real-time phenomena of the lived experience. Poor health outcomes that come from environmental pollutants are not just about the measurable symptoms or the environmental metrics, it is a full sensorial phenomenological experience. There is the anxiety of being exposed, the distress from suffering health issues that are not yet understood, the fatigue from not being able to rest from the various stressors, and so on. Therefore, to assume that data will be able to reflect all of this information is naive and can lead to propagating health injustice. In cases of health justice, we need an equitable and informed consensus on the phenomena at an appropriate scale (i.e. global versus local presence and impacts of air pollution, diabetes cause and severity amongst racialised and gender categorisations). The role communities, as experiencers of the phenomena, play an important role in giving the data context and helping data specialists and practitioners support claims on how well data is fulfilling its purpose as a proxy for phenomena. Accountability can come from assessing the output of devices to recounting individual experiences as a comparison to data findings.

8

There is a need to address the bias in healthcare and data. When dealing with data and health, in particular, there are several forms of biases that we have to be cognisant of if we are to achieve the right cognitive framing for health justice. Evidence has shown that healthcare professionals can show the same levels of implicit bias, meaning associations made outside of conscious awareness, as the wider population. This is an issue because it leads to those racialised as Black and Indigenous to experience negative health outcomes such as lower quality of care (source, source, source) and higher rates of childbirth mortality (source, source). The National Academy of Medicine has published several commentaries and discussions over the years to help bring light to how we approach the structural and implicit biases of healthcare, including an article on creating space for early career healthcare professionals to consciously engage the “isms” in the field that marginalise patients (source). Unless these biases from healthcare professionals are acknowledged and addressed, the health data will not be a path to health justice for many who need it the most. Even well-intentioned exploratory data comes with biases that affect the use by communities. (source).

“There is the anxiety of being exposed, the distress from suffering health issues that are not yet understood, the fatigue from not being able to rest from the various stressors, and so on. Therefore, to assume that data will be able to reflect all of this information is naive and can lead to propagating health injustice.”

From Data Supremacy to Equitability

In the introduction we looked at the need to dismantle the supremacy foundations of data and science, if we are to achieve equitable Healing Futures. In this section we will look at two frameworks; the DIKW Model and the scientific method.

DIKW Model for Health

The goal is to help those looking to provide health justice to individuals and communities through data understand where their work and findings fit into the greater aim of a community where we can make health justice decisions based on wisdom. An additional goal of the health data DIKW model is to help clarify distinctions between data and more contextual, higher dimensional terms.

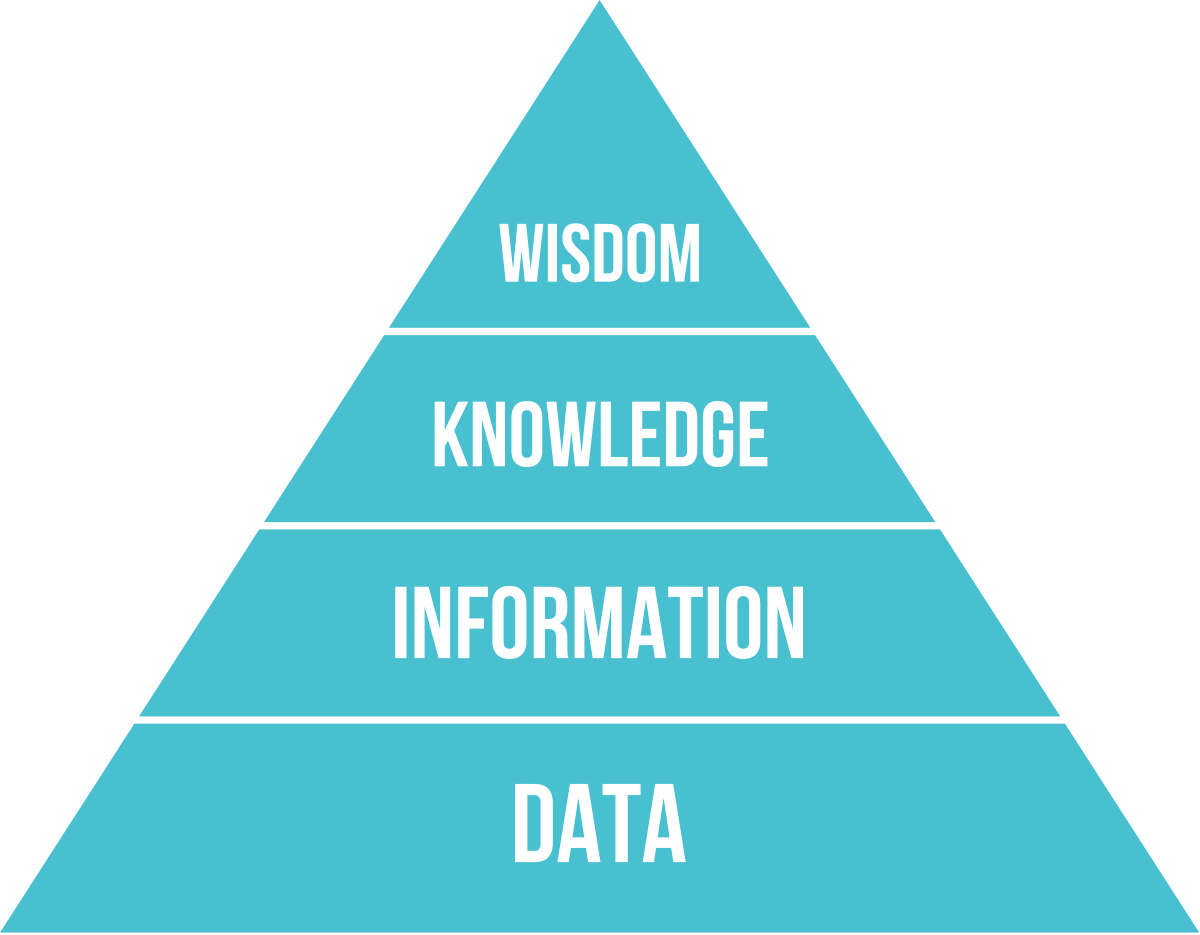

DIKW Model

Source: Wikipedia

The DIKW model, which was created in the late 1980s, is referenced in Milan Zeleny’s Management Support System (source). Though not originating in the health domain, the DIKW model is a useful framework, because it provides stages in which insight is needed to provide greater purpose to what starts as data.

The model presents four stages: Data, Information, Knowledge, and Wisdom. We acknowledge that in practice the lines between each layer may not always be clear cut. There are two approaches to navigating from one stage of the DIKW model to the other (source), the latter appearing to be the most viable and relevant to the goal of health justice.

The first is to increase the metrics. This means that if you gather enough isolated data points, it becomes information. Create enough information by paired sets of linked data and it becomes knowledge. Gather enough knowledge from those knowledge clusters and it becomes wisdom. In order for this flow to work at each step there must be discussion and reassessment, otherwise, there is a risk that we carry misinformation from the data stage to the wisdom stage.

The second approach involves dimensions. This movement is more of a qualitative transcendence up the model. That is because it relies more on our intuition and cognitive parsing of concepts. For instance, you might decide that transcending from information to knowledge is understanding the model of a car, the owner of a car, and the times it is parked outside as information contributing to knowledge that your neighbour parks their car of a certain model in that location every weeknight. In a health context, knowledge could be that someone is ill or that you know what the general traits of an ill person are. Wisdom then becomes your heuristic for how you respond to these situations. Wisdom grows as more experiences develop your knowledge. In a health sense, you might develop wisdom on how to maintain your health during the week by various situational knowledge of your environment and your own body.

This approach is in alignment with how communities can develop community sovereignty over their own form of health justice.

Below is an extrapolation for a Healing Futures context.

Health Data

To build data practices that enable and promote health justice, ethics and due diligence must start with ethical health data collection. In ethical data practices the data is collected with community consent and comfort. Even though the data itself may be unstructured and of little value in isolation, a community must feel safe in the data being generated and collected. External collectors need to be mindful of cultural barriers around certain data collection practices and treat community concerns as an opportunity to create data novel collection practices. A community may, for instance, not allow researchers to talk to children alone but be happy to develop prompts that they can provide to children and return with answers. Keeping an open mind at the beginning increases the likelihood that the data collection practices are in cultural alignment, the first step towards a community being comfortable using that data for health justice purposes.

Health Information

The health information has explicit meaning around the data, which makes the data identifiable. Security and community consent become fundamental to the development of health information. Common practice would be to use terms from the scientific literature to describe each piece of information. If our goal is community health justice, there needs to be a translational phase where practitioners either teach the community the terminology or translate the terminology to how the community already identifies that type of information. In action, this would include being knowledgeable about the linguistic and cultural frameworks a community has around the data being collected.

On a more technical level, you may have to format information to be more digestible. An example would be presenting data as daily average temperatures or caloric intake to respond to a community’s preference as hourly readings are too discrete and a community does not think of most health information in hours. Sometimes, the best option might be to collect at a discrete level then put the information forward to a community and have them put it into their own context. Another technical consideration is that some communities will respond to diagrams, charts, or scales better than discrete numbers. With all of this in mind, a community is also capable of changing its culture around certain types of information.

After all of these considerations lead to the conclusion that health information needs to be cognitively and physically accessible. This can be the focus of campaigns and interventions in its own right as many communities when given the avenue would happily develop their understanding of key health information as the research develops and lived experience is documented. Health information can be presented at cultural events, as school curricula, or even in popular media online where people are already engaged. This health information strategy sets communities up to be comfortable with the information as they develop the insight to achieve health justice.

Health Knowledge

Health knowledge means that people have the framing and relevant information to start making a running assessment of their health. If we have accessible and equitable health information, health knowledge is how this information is put together and viewed in relation to others. Health information is the stage where the data/phenomena dichotomy becomes important. Research tends to base our health knowledge relative to an expected norm. In general, this is useful because if someone is trying to determine if they are healthy, we can use the average physiological readings of researched populations.

The data/phenomena dichotomy emphasises why health knowledge needs to be framed by communities. There is less agency in critically assessing information and prioritising phenomena when an external party, such as a health organization or local authority, determines the health knowledge of a community.

Health Wisdom

When we are able to co-create health wisdom with communities, we will have taken a significant step towards health justice. A community that is enabled in health wisdom understands how they can make decisions about their health and communicate their current health based on all the resources provided. It changes the way organisations convey information from current data and the role that information plays in updating health knowledge.

“When we are able to co-create health wisdom with communities, we will have taken a significant step towards health justice.”

The Scientific Method

One of the brilliant qualities of the scientific method is its intuitive nature. Most of us when faced with a new phenomenon will go through the scientific method to make sense of it. We will observe, ask questions, do some research, generate a hypothesis for the phenomenon, generate an experiment or test of the hypothesis, analyse and assess. We see this method in practice across various communities that are facing an environmental and health injustice. Many will find ways to independently monitor their symptoms, the source of the pollution, and rally their community to extract various knowledge.

Here we explain both how communities use the scientific method and how as practitioners we can elevate it to better support communities facing poor health outcomes.

Observe

Humans are cognitively equipped to observe the events and conditions around them, this is especially useful in identifying a change or a threat in the environment. Therefore, a community that is facing a contamination event that is causing poor health outcomes has the cognitive capacity to observe the changes. It seems obvious, however, so many practitioners gaslight and diminish community intellect.

Communities are experts of their domain as they are able to observe their environment on a daily and constant basis. Therefore, they make effective whistle blowers and are often first to point out a health hazard. Practitioners in turn should learn how to equitably, consensually, and effectively extract these observations from the community and apply them to the initial questioning and hypothesis stage.

Ask a Question

Any investigation starts with a question. In our observations, communities are very adept at asking pertinent questions related to the phenomenon they are experiencing; is prolonged exposure different than short term exposure, why are some of us getting sick and others not, are those closest to the site more at risk, are the right factors being monitored, etc. Our role then as practitioners is to take these questions and tease out the most scientifically plausible in collaboration with the community. For example, when working with CASH, we focused not on the measurable risk of the contamination, because this would take too long to investigate, but on framing air pollution as a health hazard regardless of exposure. This line of research was teased through listening to the community’s needs and through our scientific experience.

Background Research

Community members, by being culturally and/or geographically close, will have relevant experiences that can influence the way a question transitions into a well-informed hypothesis. There may also be reports, investigations, stories, etc, from other sources relevant to the question at hand.

Hypothesise

A hypothesis in health justice comes from a combination of the lived experience and access to background research which can highlight trends from other communities or community members that support the expected condition.

The infrastructure should already be in place for reliable knowledge management.

Collect / Experiment

Collecting must respect the culture and safety of the community. Communities will have their own tools and methods for certain types of data collection, particularly when it involves vulnerable populations. Therefore, it is important for the practitioners to adapt their collecting and experiment methodology to the needs and consent of the community. Examples could mean using visuals instead of spoken data collecting, co-creating novel toolkits, or instructing community members on self-reporting in safe spaces.

Analyse

In our observations, many communities have not been able to trust the analytical processes used regarding their health as they can contradict their lived experience. Therefore, it is imperative that practitioners maintain transparency and constant communication with community members from beginning to end when analysing the health condition of a community. Finally, the continual engagement can also prevent errors in the analysis. Errors being an analysis that contradicts the lived experience of the phenomena.

Draw Conclusion

A conclusion is simply accepting or rejecting the data-led hypothesis, not deciding if the phenomenon exists. This nuance is why the data-phenomenon dichotomy is very important for both community members and practitioners to keep in mind.

Communicate Results

The results can be disseminated in papers but also needs to be in media and avenues accessible to the community so it can become background research for future investigations. The more communities that disseminate their investigations, the richer the quality of background research and case studies available for people to use when creating their own health knowledge leading to health justice.

Summary on Health Justice Data Practices:

Take the due diligence to establish the phenomena before deciding on data to collect and analyse.

Communities can practice scientific methodology to their health with the right avenues.

Knowledge management should be an individual and community process when it comes to health.

It is not the job of practitioners to decide the cultural framing of health, it is a conversation to develop with communities.

Concluding Statement

Whilst data and its processes can be seen as apolitical and unbiased, their application often is not.

Therefore, as practitioners we must be aware of this risk in order to avoid propagating health inequities and injustice.

A sure way to reduce this risk is by collaborating with communities and breaking down the supremacy rapport that is the norm.

We must respect, acknowledge, and use community knowledge, tools, and expertise throughout the various data processes.

Only by playing our part in providing accessible, transparent science can we build the trust to help communities create their own health justice.