Obesity & Trauma

A report by Charlotte Kemp, Daniel Akinola-Odusola, & Araceli Camargo

2022

Before reading this report please note that we are a non-profit grant and citizen supported programme, we use our funding to create free scientific reports, which provide foundational knowledge about health, health inequities, and health justice. We prioritise the hiring of scientists and researchers from marginalised communities to ensure that the lived experience is covered in an ethical, inclusive, and accurate manner.

Our goal is to be an open lab that is “for the people by the people”. Your contribution helps make that happen.

Introduction

650 million people worldwide have obesity with 39 million being children under the age of five (source).

Obesity now has a global presence, with a “substantial rise in most countries”, as a result obesity is now classified as a pandemic with numbers set to rise unless we learn to tackle the problem (source).

To solve a problem, it first must be understood and defined accurately, at the moment this does not seem to be the case when it comes to obesity.

Firstly, due to having an observable phenotype, it is often labelled and defined as a weight problem.

Secondly, this definition leads institutions and healthcare organisations to only concentrate on food and exercise rather than other systemic ecological factors such as exposure to pollutants and trauma.

Finally, this gross simplification leads to a cultural framing of obesity as a personal lifestyle choice, which in turn creates a culture of stigma rather than healing.

This report will take an ecological approach, focusing on the bidirectional pathway between trauma and obesity to highlight the disparity between scientific evidence and communication around obesity, as well as the psychosocial factors that contribute to, and maintain, this disparity. This is to ensure health organisations and policies support a holistic and equitable prevention strategy for obesity.

What is Obesity? Some Basic Understandings

Obesity is a dysregulated production of adipose tissue commonly known as fat throughout the body. It is considered a complex and chronic disease, which means there are multiple factors that contribute to its aestology (source). Additionally, it means that various biological systems are involved in its initiation and progression (source).

BMI

BMI is still the prominent technique for diagnosing obesity. It is the body weight in kilograms divided by the height in metres squared. The problem with BMI is it does not give insights or knowledge on the biological functions that contribute to the disease. Secondly, it does not measure the overall fat or its distribution. Despite these failings, BMI is still the main strategy for obesity diagnosis. (source) (source 1)

Obesity as a Risk Factor

Obesity can be a risk factor to cardiovascular disease, insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes, stroke, and Cushing’s syndrome, depression, and dementia. (source)

More Than a Weight Problem

Obesity can cause low-grade chronic inflammation through increased circulating fatty acids, and chemoattraction of immune cells that contribute to the inflammatory condition.

Inflammation when it is working within a normal range, helps sustain the function of tissues and organs. It is also a protective response to an injury, infection, or irritation (source)(source).

However, when it is chronic it can dysregulate various body functions. This is a core component of what makes obesity complex and a risk for other diseases. (source) (source)(source)

Obesity & Microbiome

There is increasing evidence indicating that gut bacteria plays a role in intestinal function, nutrient synthesis, and insulin regulation.

Additionally, gut bacteria has been linked to chronic low level inflammation, which creates systemic exposure to bacteria ipopolysaccharide derived from the intestinal microbiota.

Interestingly, trauma or acute stress exposure have been linked to changes in our gut environment. (source) (source) (source) (source)

What is Trauma and Why it is Important to Obesity

In psychology, trauma can be defined as the reaction to a deeply distressing or disturbing experience. In medicine, trauma is defined as a physical injury. Although the experience of trauma as described by these fields may at first seem discrete, they are largely intertwined. As well as the fact that they often co-occur, physical and psychological trauma are bi-directionally related perpetuates of the other. For example, the experience of a physical injury often triggers a psychological response and the experience of psychological trauma triggers a physical innate immune response. Accordingly, “the future might thus yield insights into multiple common and interactive immune responses, including immuno-metabolic and neuro-immunological switches and checkpoints after physical and psychological trauma (source).”

Common examples of trauma experiences include physical and sexual abuse, verbal or emotional abuse, childhood neglect, intimate partner violence, accidents or disasters, illness, incarceration etc. Further, there are several ways in which these traumatic events are experienced (e.g. see source, source). These include the direct experience of single (acute trauma) or multiple (repetitive trauma) traumatic events either as an adult or as a child (developmental trauma). Further, trauma can be experienced through close individuals (vicarious), particular groups or populations (historical trauma, collective trauma) as well as generations (intergenerational trauma).

Trauma also creates systemic biological and cellular changes. For example, it can change our gut bacteria environment, which has implications for obesity (source). In cases of acute trauma, some can experience PTSD, which creates neurobiological abnormalities which alters the function of various biological systems, this too has implications for obesity (source). The link between obesity and trauma also provides a wide ecological scope to understand the different determinants of a disease that is complex and not just a “lifestyle choice”.

Systemic Trauma & Structural Violence

Trauma can come from direct pathways as described in the section above, however it can also be systemic. Norwegian sociologist, Johan Gultang, introduced the term structural violence in the 1960’s to describe the outputs of racism, classism, sexism, and other marginalisations (source). He defined structural violence as an “avoidable impairment of fundamental human needs” (source). For this report we are identifying the following systemic trauma pathways, we understand there are more, however this table illustrates there are various trauma based determinants for obesity.

-

Description

Pollutants in outdoor and indoor air from vehicles, constructions, transport, indoor furnishings, cleaning chemicals, or cooking methods.

Relation to Obesity

Air pollution can cause chronic inflammation as well as affect the gut environment.

-

Description

Over exposure to light at night from buildings, street lighting, or traffic.

Relation to Obesity

Disturbances to sleep wake cycle, which can create biological changes in the body that heighten the risk of obesity.

-

Description

A home that does not provide dignified shelter; mould, poor infrastructure, dilapidated or no shelter at all.

Relation to Obesity

There are multiple relationships.

Lack of sleep which affects sleep/wake cycles.

Stress from experiencing constant insecurity.

Respiratory difficulties from mould, which can lead to lethargy or low energy. This in turn could have an effect on physical activity. Mould can also increase inflammation in the body.

-

Description

Not being able to afford to heat or cool your home. It can also prevent access to cooking facilities.

Relation to Obesity

There are multiple relationships

Poor quality sleep due to thermal discomfort, this can affect the sleep/wake cycle.

Stress from not being able to access a vital resource. The stress can lead to inflammation.

There is also the inability to cook fresh food due to lack of energy. This too can cause stress as well as put people at risk of food insecurity.

-

Description

Irregular work patterns that includes night work.

Relation to Obesity

There are multiple relationships

Shift work often means essential work which can expose people to indoor or outdoor air pollution. E.g. Hygiene workers/drivers.

Shift work can also mean working at night exposing people to light and noise pollution.

This type of work can also cause a disruption to the sleep/wake cycle due to working nights.

-

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41366-018-0089-y

https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s40572-018-0215-y

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0306987711004762

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6489456/#:~:text=A%20short%20sleep%20period%20has,particularly%20in%20younger%20age%20groups.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6489488/

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B9780128125045000015#:~:text=The%20obesity%20associated%20fat%20accumulation,that%20worsens%20the%20inflammatory%20processes.

https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamapediatrics/article-abstract/190117

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0140988321003212

https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/full/10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.225698

https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/full/10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.225698

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S2212267215000064

https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/full/10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.225698

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6489488/

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41366-018-0089-y

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6489456/#:~:text=A%20short%20sleep%20period%20has,particularly%20in%20younger%20age%20groups.

Stress, Trauma, and Obesity

We have seen how trauma is both physical and biological. Further examination of the biological cascades that precede and follow the experience of stress and trauma provide insight into some of the pathways which facilitate and maintain the increasingly apparent relationship between trauma and obesity. For example, as can be seen in Figure 1, the consequences of trauma exposure and subsequent chronic stress include dysregulation of glutamate transmission, dysregulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis and pro-inflammatory processes - all of which have been associated with obesity.

Figure 1 - Vicious cycle of trauma (source)

Inflammation, for example, is our body’s ability to protect against infection. However, its dysregulation (that is the alteration of its original function) has fundamentally changed our view of the underlying causes and progression of obesity and metabolic syndrome.

We now know that an inflammatory program is activated early in adipose expansion and during chronic obesity, permanently skewing the immune system to a proinflammatory phenotype, and we are beginning to delineate the reciprocal influence of obesity and inflammation. Reviews in this series examine the activation of the innate and adaptive immune system in obesity; inflammation within diabetic islets, brain, liver, gut, and muscle; the role of inflammation in fibrosis and angiogenesis; the factors that contribute to the initiation of inflammation; and therapeutic approaches to modulate inflammation in the context of obesity and metabolic syndrome.

Another trauma/obesity biological pathway is through the dysregulation of the HPA-Axis and its associated hormones that are essential in the distribution and breakdown of body fat (source). An example of how this pathway can play out can be seen in Figure 3.

Figure 2. An example pathway between sexual assault and obesity (see source for a full outline)

Understanding these perturbations in obesity is particularly important given that dysregulation of the HPA-Axis is a risk factor for physical health conditions such as cardiovascular disease, insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes, stroke, and Cushing’s syndrome.

These examples provide a demonstration of some of the ways in which trauma is associated with obesity. It is, however, important to note that this association is not linear, nor is it simple. Although a comprehensive model of the complex and multifaceted interaction between trauma and obesity (as well as the risk/protective factors for experiencing them) is beyond the scope of this report, Figure 2. Provides insight into the trauma / obesity cycle. It also highlights how structural violence pathways have a biological component.

Figure 3: Trauma/obesity relationship and feedback loop (including structural violence determinants)

An important observation is that trauma and obesity are bi-directionally related through pathways involving the disruption of psychological and biological systems. Further, Figure 3. shows that the experience of obesity and trauma play into a feedback loop.

These relationships begin to elucidate not just the formation, but the maintenance, of the trauma obesity association.

Childhood Obesity: A London case study

Obesity can lead to other equally complex diseases, therefore understanding obesity in the context of childhood is paramount in reducing later life diseases. Obesity is being diagnosed at younger and younger ages, which given what we have learned in this report, raises a question of morality. What type of society do we want, one of healing or one of chronic health injustice?

The objective of this analysis was to understand the relevant trends and comorbidities of places with high environmental stress factors, psychosocial stress factors, and the prevalence of severe childhood obesity - all of which are trauma determinants. This trend analysis is meant to complement the work done in identifying local and individual relationships between these different outcomes that can’t be captured in macro data.

The obesity data is based on surveys and is used as a sample to represent the obesity prevalence on a local authority level.

City of London data is joined with Newham in this data. Additionally, Reception data unavailable for: Enfield, Newham, Sutton, Wandsworth. Year 6 data unavailable for: Enfield, Wandsworth. These omissions are visible in the respective maps.

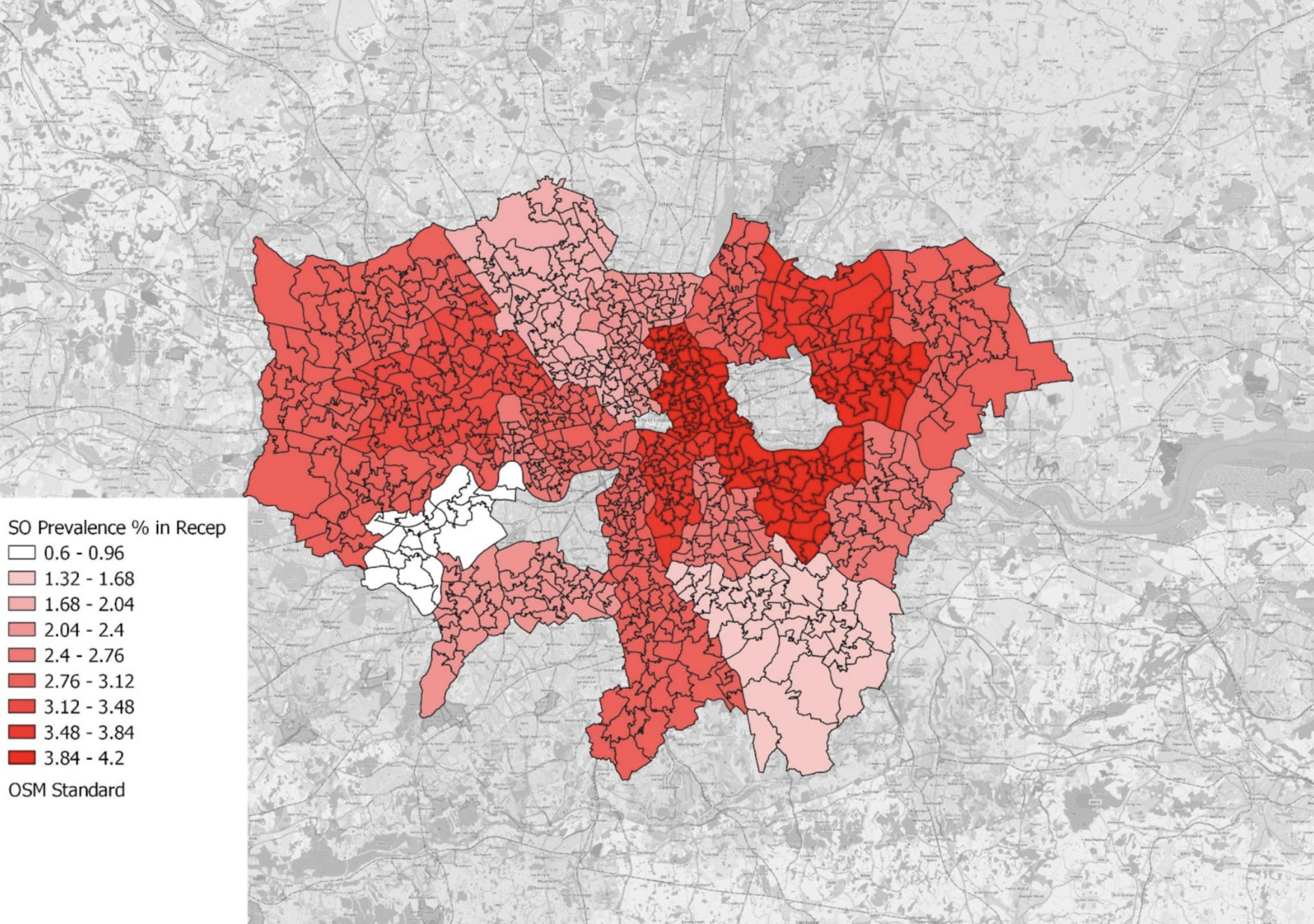

Severe obesity prevalence in reception (aged 4-5) children, London 2019-2020, by ward.

Insight: Percentage prevalence with a high of 4.2%in Barking and Dagenham, 4.1% in Greenwich, and 4% in Hackney and Tower Hamlets.

Severe obesity prevalence in year 6 (aged 10-11) children, London 2019-2020, by ward.

Insight: Hackney, Barking and Dagenham, Greenwich, and Tower Hamlets topped both reception and year 6 maps for severe obesity prevalence.

Severe obesity prevalence increases overall between the ages as the max is 4.2% and 8.0% for reception and year 6, respectively.

Top left map is Index of mass deprivation by ward and top right is the Biological Inequity Index (environmental stressors and IMD combined. Bottom left is year six obesity map and bottom right reception age obesity map. All at ward level.

Trends:

For year 6 (bottom left) we can see a trend of high obesity prevalence with high deprivation. Deprivation has various trauma pathways.

When we combine environmental stressors and deprivation, which is an environment that has high concentration of stressors or trauma pathways, we can see the trend of obesity being prevalent in areas of multiple stressors become more pronounced.

The same is for reception age (bottom right), except for the Southeast. This would be an interesting place to do a lived experience study to understand what other determinants are at play to cause children to be diagnosed with obesity.

The Current Language & Narrative of Obesity

This report has presented why obesity is a complex disease with multiple interacting contributing factors, many of which are completely out of the control of the individual. Despite the vast and robust evidence, obesity is still heavily stigmatised with people often being made to think this incredibly complex disease is their fault.

This stigmatisation starts in the science journals and moves to the doctors office and spills out to socio-cultural psyche. In a letter to the editor for the Journal of Primary Care and Community Health, the authors point to a recent paper titled Childhood Obesity: An Evidence-Based Approach to Family Centred Advice and Support - which in their words the paper “highlighted how biases amongst physicians can lead to stigmatising beliefs, which blame individuals for exercising insufficiently and eating excessively” (source). They go on to state how this thinking is unhelpful as the shame can lead to obese patients not seeing medical help and it ignores the upstream determinants (source). However, the upstream determinants fail to go beyond diet or access to diet.

When it comes to the socio-cultural psyche, the stigmatisation also manifests in reducing obesity as a weight problem that is solved by dietary changes. In a recent campaign by Cancer UK, obesity was metaphorised into cigarette packets full of fries (chips). This creates a socio-cultural framing of obesity that blames a person not only for having obesity, but also for subsequently putting themselves at risk for cancer. This is not only psychologically harmful to those experiencing cancer and obesity, it is also scientifically inaccurate.

Another example of the problematic depiction of obesity can be seen in how it is explained by the National Health Service in the United Kingdom. For example, the health A-Z about the causes of obesity (source) focus on individual behaviours and choices by saying that obesity is generally caused by “eating too much and moving too little” and is “ a result of poor diet and lifestyle choice”. In a further section, it says “some people claim there's no point trying to lose weight because it runs in my family or it's in my genes. While there are some rare genetic conditions that can cause obesity, such as Prader-Willi syndrome, there's no reason why most people cannot lose weight.” There are two problems with this statement, the first is that it fails to give a clear explanation about the complex interplay between genes and environmental factors. Secondly, it firmly puts the blame on the individual. A national health service cannot use inaccurate messaging or narrative as it contributes to health injustice and further marginalisation.

Centric Lab touched on this issue in a research article (see here) where we highlighted the links between obesity, classism and racism.

Health Justice Considerations

Not only is it hugely unpleasant, the stigmatising obesity narrative as outlined above serves as a barrier to public health and health justice in a number of ways.

It is simply inaccurate

As this report demonstrates, it is becoming clear that complex interactions of environment, neurohormonal systems, and trans-generational effects directly contribute to obesity (source). It is simply inaccurate to depict obesity as a problem of “the individual” and, in doing so, the real contributing factors (and thereby solutions) are not explored. Consequently, the problem persists.

It exacerbates the problem

People feel fearful, ashamed and blame themselves - can lead to low self-esteem, stress and mental health problems that feeds into feedback loop

People don't seek healthcare, and the healthcare they receive can be poor as a result of bias

It sustains inequality

The obesity and individual blaming narrative helps to deflect from, and sustain, oppression, health inequities and structural violence.

Blaming the individual means that the systems which actually cause the problems (e.g. capitalism, supremacy) can persist without challenge

Focus on Systemic Strategies and Investigations

Changing the narrative - language is a good place to start - say “living with obesity” rather than “you are obese”

Change the messaging from one that says obesity is a “lifestyle choice” to one that defines obesity as a chronic and complex disease.

Build empathy through robust science and an ecological framing of obesity.

Create systemic solutions such as energy poverty campaigns or better worker rights.

NHS should partner with urban planners to policies that reduce air pollution and light pollution in cities.

Fund more research to understand further the structural violence determinants of obesity.

Fund more geospatial studies to understand where in cities obesity is clustering to further understand its ecological determinants.

Fund lived experience studies that tell the stories of those living with obesity to both change the narrative and understand further ecological determinants.

Investigate what greater health risks are brought on by being severely obese during childhood development in a deprived environment?

What are key factors that create the prevalence in the highest local authorities?

What are the lowest obesity prevalence local authorities doing right as an environment?

All About Obesity with Sarah Le Brocq

Sarah Le Brocq is a person living with obesity and is the founder of All About Obesity (allaboutobesity.org), is a Director & Lay Member at NICE - National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, and member of the All Party Parliamentary Group of Obesity in the UK.

Charlotte Kemp sat down with her to speak on her experience with the disease as well as how she is moving towards health justice.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Charlotte Kemp

Charlotte has a first class BSc in Psychology and received a distinction for her MSc in Cognitive Neuroscience. Charlotte has over 6 years of professional experience of working with people with mental health problems, epilepsy and a variety of disabilities, in several settings.

Araceli Camargo

Araceli is lead scientist at Centric Lab and a cognitive neuroscientist focused on how people interact with urban environments. Araceli Camargo is of Indigenous American descent and holds an MSc in Cognitive Neuroscience from King’s College London.

Daniel Akinola-Odusola

Daniel is lead data scientist at Centric Lab. Daniel’s role is developing Centric’s software as well as ensuring all data is correctly gathered, interpreted and communicated. Dan holds a MSc in Neuroimaging from Kings College London.